Economic growth – doesn’t it sound lovely? But is sustained, continual economic growth really possible?

Really, the whole to’ing and fro’ing over budgets needed for economic growth and austerity measures and just who is paying for it all has been about this fundamental question. It underpins all sorts of debates about not only Australia’s contentious 2014 budget but all those post global financial crisis budgets round the world. It’s a question that has spawned Wall Street protests and Hong Kong sit ins, devolution of power grids into small communal solar (or other renewable energy sources) generation of electricity in places such as Wildpoldsried (pop. 2,600) in Germany and a Greek election of a left wing government. According to Fred Magdoff and John Bellamy Foster, 2011, in What Every Environmentalist Needs to Know About Capitalism, the idea of continual economic growth teaches ‘that greed, exploitation of laborers, and competition (among people, businesses, countries) are not only acceptable but are actually good for society because they help to make our economy function “efficiently”’. What would happen if our economy stopped growing over a very long term – if our finances hit a particular level and then remained there; if there were no more line graphs shooting skywards? Would it be an end to efficient economic management? This is what is called a steady state economy, one where economic growth is no longer continual. Would this be the disaster many of the world’s treasurers predict? Would there be no more food, an end to development, terrible losses of jobs, stagnation and ruin, wars and famine?

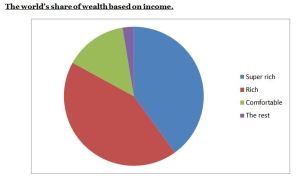

Probably not. A steady state economy would (according to Investopedia, 2015) equal ‘an economy structured to balance growth with environmental integrity…’ [finding] ‘an equilibrium between production growth and population growth. The economy aims for the efficient use of natural resources, but also seeks fair distribution of the wealth generated from the development of those resources.’ Is economic growth in fact a myth? The reality is that most of us, over the past thirty or so years, have not actually experienced real economic growth – our finances haven’t actually improved. It’s a con. What’s actually happening is that a few peoples’ finances are improving (quite nicely, thank you very much) but many of the rest of us are actually getting relatively poorer. In fact, most of us are actually experiencing not only economic decline but we’re watching the world go to the crapper environmentally. The disparity between rich and poor has not merely grown internationally; it has also increased within nations. Chrystia Freeland notes in her book, Plutocrats, The rise of the new global super rich (2012) that the average 1980 CEO in the US had a wage 42 times the average income in the country; by 2012, the multiple was 380. According to the UK’s Guardian newspaper there has been a 117% increase in wages for the wealthiest 1% of Brits (in real terms) since 1986, compared with an average wage increase of 47% for the rest of the population. The Poverty program estimated that, in 2011, 1 in 7 people in the European Union lived in poverty, while the ratio was 1 in 6 in the US. The problem with the steady state economy idea is that most people see that getting ‘the equilibrium between production growth and population growth’ would involve increased government interventions in the economy, and we have been trained not to like governments intervening. We have been tutored in accepting the hands-off, business-knows-best neo-liberalism most of us experience these days. I’ll leave a final observation on the big question to Greens Senator Adam Bandt (ABC, AM program, 2014). He says: ‘[Billionaires tell us] …the only way we can make ends meet in the country is if ordinary people pay more and people like Gina Rinehart herself pay less… The government’s revenue is decreasing and it’s threatening our ability to fund the services Australians expect. We’ve got two choices: we can either say people like Gina Rinehart ought to pay a fairer share, or we can start cutting back on health and on schools.’But it could work and at least one of the key ways of getting this equilibrium is likely to be popular with the hoi polloi: fairer tax rates… Do we want to cut back on health and education? Do we want to live on a permanently soiled planet? So, do we really need to keep growing financially – pursuing the false utopia of eternal economic growth? The answer is no.

Probably not. A steady state economy would (according to Investopedia, 2015) equal ‘an economy structured to balance growth with environmental integrity…’ [finding] ‘an equilibrium between production growth and population growth. The economy aims for the efficient use of natural resources, but also seeks fair distribution of the wealth generated from the development of those resources.’ Is economic growth in fact a myth? The reality is that most of us, over the past thirty or so years, have not actually experienced real economic growth – our finances haven’t actually improved. It’s a con. What’s actually happening is that a few peoples’ finances are improving (quite nicely, thank you very much) but many of the rest of us are actually getting relatively poorer. In fact, most of us are actually experiencing not only economic decline but we’re watching the world go to the crapper environmentally. The disparity between rich and poor has not merely grown internationally; it has also increased within nations. Chrystia Freeland notes in her book, Plutocrats, The rise of the new global super rich (2012) that the average 1980 CEO in the US had a wage 42 times the average income in the country; by 2012, the multiple was 380. According to the UK’s Guardian newspaper there has been a 117% increase in wages for the wealthiest 1% of Brits (in real terms) since 1986, compared with an average wage increase of 47% for the rest of the population. The Poverty program estimated that, in 2011, 1 in 7 people in the European Union lived in poverty, while the ratio was 1 in 6 in the US. The problem with the steady state economy idea is that most people see that getting ‘the equilibrium between production growth and population growth’ would involve increased government interventions in the economy, and we have been trained not to like governments intervening. We have been tutored in accepting the hands-off, business-knows-best neo-liberalism most of us experience these days. I’ll leave a final observation on the big question to Greens Senator Adam Bandt (ABC, AM program, 2014). He says: ‘[Billionaires tell us] …the only way we can make ends meet in the country is if ordinary people pay more and people like Gina Rinehart herself pay less… The government’s revenue is decreasing and it’s threatening our ability to fund the services Australians expect. We’ve got two choices: we can either say people like Gina Rinehart ought to pay a fairer share, or we can start cutting back on health and on schools.’But it could work and at least one of the key ways of getting this equilibrium is likely to be popular with the hoi polloi: fairer tax rates… Do we want to cut back on health and education? Do we want to live on a permanently soiled planet? So, do we really need to keep growing financially – pursuing the false utopia of eternal economic growth? The answer is no.